Lane keep assist and adaptive cruiser control have become ubiquitous in new cars. Then why is it taking so long to make the jump to full self-driving?

The Promise and Peril of Autonomous Vehicles

The advent of autonomous vehicles (Avs) can be read alternatively as utopian or dystopian. If you’re a car enthusiast, the loss of control and connection to the activity of driving is anathema. And yet, the promise of eliminating the inherent dangers of human control, be it drunk, distracted, or aggressive driving, is too valuable to ignore in terms of human lives and, for the companies racing toward an autonomous future, in terms of money.

A few short years ago, the pace of technological innovation and investment had the industry on a fast-track to automation. Presidential candidates predicted an imminent collapse in the trucking profession as self-driving semis would take over our highways in just a handful of years. Car companies touted the latest in driver assistance technology as one small step away from fully autonomous vehicles.

As with the slow-rolling EV revolution, it appears the salespeople have gotten out over their proverbial skis, overpromising and underdelivering on the next big thing in personal transportation. Today, billions in autonomous vehicle R&D investments are being rerouted elsewhere as scandalizing headlines cast doubt on the viability of a fully autonomous future. So, where’s your self-driving car? It turns out, it’s both already here and a long way off.

Levels of Autonomy

Before we dig into the challenges facing autonomous vehicles, we need to cover what we mean by autonomous. The SAE or Society of Automotive Engineers classifies the levels of vehicle autonomy on a 0-to-5 Level scale. At Level 0 you have antilock brakes and blind spot warning systems. Level 1 covers new technologies like lane centering and adaptive cruise control, where the car takes over some braking, steering, and throttle inputs.

Level 2, the current level of autonomous driving tech deployed by carmakers, is the realm of “hands-free” driving. More throttle, steering, and braking inputs are taken over by the vehicle, but a human driver is still required to take over control of the vehicle at a moment’s notice.

Level 3 autonomy is one step above Level 2 in terms of “hands-free” driving. While a human driver is still required to monitor the vehicle and take over in complex driving situations, Level 3 autonomous vehicles will be capable of executing in more varied driving scenarios without human intervention. Car companies are currently developing Level 3 autonomy for production vehicles while awaiting full regulatory approval.

Levels 4 and 5 are a bit further off but are also no longer the province of science fiction. Level 4 autonomy would be advanced enough to no longer require human intervention, but would be “geo-fenced,” that is, limited to specific routes and well-mapped locales. Level 5 is the final utopian achievement of a world without human drivers, where all personal street-level transportation is automated.

Two Roads for AVs

The above levels of vehicle autonomy might appear clean and clear, but the current reality thereof is a lot messier. There are two independent but related tracks within autonomous vehicle development. The first you’ve probably experienced firsthand, those Level 1 and Level 2 systems already implemented in today’s passenger vehicles. These “driver assistance” systems are part of the technology’s evolution, both habituating drivers to greater levels of vehicle autonomy and allowing carmakers to refine hardware and software with the goal of safe and reliable Level 3 and Level 4 autonomy.

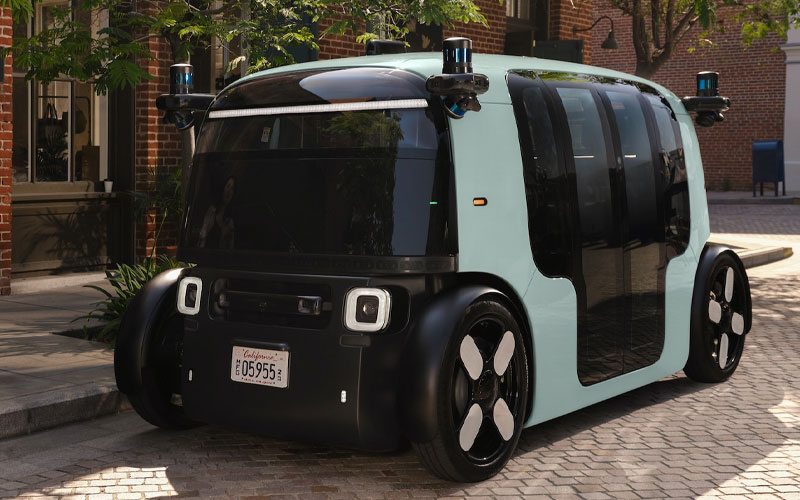

The other track in the development of autonomous vehicles is a bit more obscure, that is unless you live in San Fransico, Los Angles, Phoenix, Austin, or other major metros where AV companies have gotten permission to field their technologies on public roads. These companies include Alphabet’s (Google et al) Waymo, Amazon’s Zoox, and GM’s Cruise division. Rather than developing from the ground up, these autonomous vehicle companies have chosen a top-down approach, getting as close to Level 4 as they can with current technology and then refining it by beta testing on public roads. The results of this approach have been predictably rocky.

Stumbling Toward Autonomy

That’s right, Waymo, Cruise, and company have, over the last few years, gotten permission from the California Department of Motor Vehicles and other state and municipal regulators to operate their AVs on public roads. Much of this beta testing initially included the use of a human driver there to intervene in case of malfunction, but as confidence grew and location data was amassed, those human drivers were removed. At the same time, these companies received permission to operate ride share services using these AVs in limited numbers (300 in the case of GM’s Cruise).

Early results have varied, depending on who you talk to. According to internal data, Cruise and Waymo say on a per mile basis, their AVs operate more safely than human drivers. Anecdotally, the results of even a few hundred AVs in busy urban traffic have been less than stellar, ranging from the weird to the patently unsafe. These include a Waymo AV running down a dog, AVs running red lights, in one instance rear-ending a bus, confused AVs halting in the midst of traffic, driving into construction zones and active crime scenes, and most troublingly San Fransico Fire and Police Departments cite numerous instances of AVs disrupting first responders.

These “kinks” came to a head October 2nd of last year when a Cruise AV critically injured a pedestrian in San Franciso. According to the California DMV, Cruise withheld information from investigators regarding the incident, prompting the revocation of their license to operate in the city. The fallout has been swift at Cruise, which paused operations, fired nine top executives including the COO, and slashed 24 percent of its total workforce as the company scales back its ambitions.

GM’s Cruise isn’t the only company having trouble rapidly advancing AVs; indeed, storm clouds have been building for years. In 2022, Ford and Volkswagen scuttled their joint AV venture, Argo AI, with both companies saying they’d be refocusing their efforts on improving existing Level 2 and forthcoming Level 3 systems.

One company, Tesla, has been determined to blur the lines between Level 2 and Level 3 or 4. Tesla’s Autopilot and Full Self-Driving systems, both Level 2 driver-assist, have been titled and marketed as though they were more capable than they are. After a more than two-year investigation into its Autopilot system by the NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration), Tesla announced late last year a sweeping recall of roughly 2 million of its vehicles to address the less-than-intensive driver monitoring features that are part and parcel of Autopilot and FSD.

Tesla has been releasing ever more sophisticated versions of its Autopilot and FSD on customer cars for years, like Waymo and Cruise, effectively running real world beta testing on public roads. Yet, according to Tesla, when operating Autopilot, their cars have averaged 1 accident per 4.5 million miles driven versus the US average of 1 per 600,000 miles drive.

From Here to There

It’s easy to point to the current hiccups with AVs and dismiss the utopian vision of ubiquitous Level 5 autonomy as mere fantasy. However, to do so is to gloss over the very real but surmountable challenges engineers are tackling today.

The biggest challenge is one of computing. The artificial intelligence (AI) used in autonomous driving systems require lots of repetition to illicit the necessary pattern recognition. According to a Rand Corporation study, that means tens or even hundreds of billions of miles driven by AVs to match the one fatality per 100 million miles driven by human drivers. Amassing this kind of data takes time and repetition which is why Waymo and its ilk have limited themselves to specific localities, mapping and mastering the cities in which they operate.

Tesla says their FSD-equipped cars have already traveled some 300 million miles, while Waymo and Cruise have combined for around 8 million miles. Even with those miles under their collective belt, some experts question whether Level 5 autonomy will be achievable without artificial general intelligence (AGI), which in turn may not prove technologically feasible.

Other technical hurdles might also prove too difficult to surmount, at least when it comes to Level 4 autonomy. Current Level 2 systems like Tesla’s Autopilot, GM’s Super Cruise, Ford’s Blue Cruise, and Mercedes-Benz’s DRIVE PILOT are all impressive…in traffic, in clear weather, on clearly marked roads. These systems operate on a combination of Lidar, radar, cameras, and other sensors to map the world around them. They are the eyes of an AV. They are also easily disrupted by inclement weather like fog, rain, and snow. Add in the unpredictable behavior of wildlife, pets, and children for even greater levels of complexity to compute and predict.

The biggest question when it comes to autonomous vehicles might come down not to the limits of technology but rather our perception of risk. Currently, data on driver assist and autonomous vehicle safety is not robust, but early stats point to a reduction in accidents. And yet, our collective tolerance for human related hazard is a lot higher than robot related hazard. People tend to weigh anecdotal evidence more strongly than they do statistics which places a perhaps artificially high bar for AV safety. Then again, given the overexuberant rollout of half-baked AVs in San Fransico and elsewhere, maybe a high bar is warranted.