When Chevrolet Bought GM (Sort Of)

You know Henry Ford changed cars, but do you know the story of how William Durant built General Motors into the world’s biggest carmaker?

Making General Motors into GM

By the 1950s, General Motors, as the world’s biggest car manufacturer, set the pace for innovation and sales in the decade’s heated competition between itself, Ford, and Chrysler, Detroit’s Big Three. The seeds of GM’s success had been sown decades earlier by two quite different men: William Durant and Alfred P. Sloan.

Back in the heady early days of the automobile, new car companies winked into and out of existence like stars in the early universe. Most were conceived and founded by monied entrepreneurs who’d caught the motorized carriage bug and, rightly, believed the automobile was the next big thing. This moment in the early 1900s illustrates the now well-worn saw that “making cars is hard.” Like the EV startups of today, most of those early carmakers ran into the same challenge: scaling their business to achieve profitability.

A few business leaders, like Henry Ford and William Durant, managed to crack the code and build the 20th century’s biggest industrial titans. Today, Ford’s path to success centered on the one-size-fits-all approach of the Model T and the adoption of assembly line manufacturing. Durant took a different approach with GM, gobbling up smaller companies, retaining their diverse product lines, and integrating their outputs. That’s not to say GM’s path to dominance was smooth or straightforward, especially for Durant himself.

How Chevy Bought GM, but GM Owns Chevy

General Motors was officially incorporated on September 16th of 1908, by William Durant. As a young man, Durant founded the Flint Road-Car Company with Josiah Dort in 1886, which eventually became the Durant-Dort Carriage Company. Together, they built the fledgling carriage maker into the biggest vehicle manufacturer in the US by the turn of the century.

Durant, once skeptical of automobiles as a loud, dirty fad for the rich, began to recognize the potential mass appeal of cars and the seemingly unexploited space for innovation within the nascent industry. To that end, Durant bought Buick, then a struggling local Flint carmaker, in 1904. By 1908, Durant had built Buick into the country’s biggest carmaker. Emboldened, Durant set his sights even higher, founding General Motors as an automotive holding company in September of that year and began its collection of brands with Durant’s Buick, followed quickly by Oldsmobile in November.

Over the next few years Durant began buying up small car companies and associated parts manufacturers; a total of 22 in all. Not all these bets paid off, but those that did paid off handsomely. The list of GM acquisitions included Cadillac, Oakland (later Pontiac), Rapid and Reliance (later consolidated with other brands into GMC), and McLaughlin (later GM Canada). Whereas Ford sought the ruthless efficiency of the assembly line putting out the singular Model T in black paint, Durant’s GM worked to offer a diverse lineup of cars (and colors) and integrate their supply chain across brands.

An attempt to buy Ford for 8 million dollars in 1909 fell through when GM’s bankers became concerned that the company was overleveraged. Not only did GM fail to secure the funding for Ford, the debacle, and perceived profligacy on the part of Durant, led to his ouster from the company he founded in 1910.

Undeterred, Durant kept his GM shares while seeking out new ventures that included approaching racecar driver Louis Chevrolet about starting a new car company. Durant’s drive and business expertise helped build Chevrolet into a successful company, successful enough for Durant to continue to invest in GM shares. By 1916, Durant and the Chevrolet corporation had acquired over 50 percent of GM stock. Durant was once again elected president of General Motors, bringing the hot new Chevrolet brand with him. He oversaw yet more acquisitions for GM including Delco Parts (1918), a 60 percent stake in Fisher Body Company, which made the bodies for GM brands like Cadillac, Oldsmobile, and Buick among many other carmakers, and Frigidaire in 1919.

A downturn in the stock market in 1920 led Durant to buy stock on margin. Eventually, his debts became unsustainable, and GM president Pierre du Pont agreed to pay off those debt in exchanged for Durant’s resignation.

Alfred P. Sloan Takes GM to New Heights

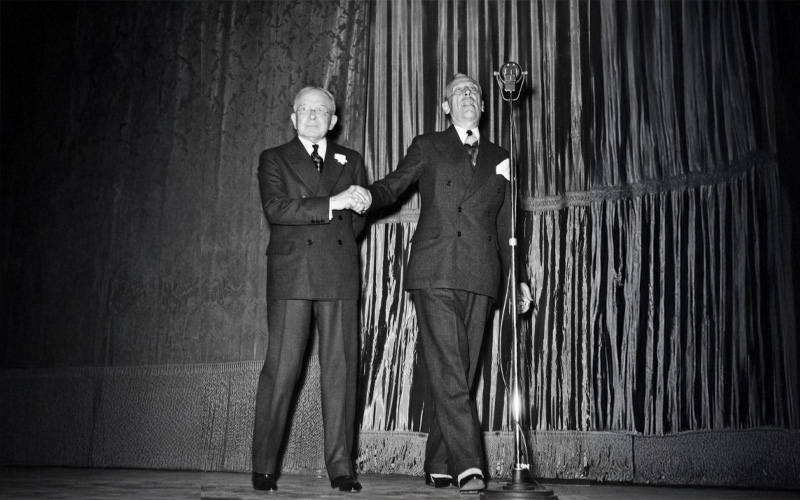

Following the ouster of Durant for a second time, Alfred P. Sloan was named VP of Operations for GM. Sloan was an MIT engineering grad who’d helped build the Hyatt Roller Bearing Company (purchased by his father in 1889 for $5,000) into a successful company which Durant and GM had then purchased for $13.5 million in 1916.

By 1923, Sloan’s stewardship of GM had been successful enough to see him elevated to CEO. Sloan’s approach for GM was to offer its disparate brands in tiers with Chevrolet as the most affordable entry point with Cadillac at the opposite end of the spectrum and Oldsmobile, Buick, and, later, Pontiac filling in the middle. Sloan also pioneered the idea of annual visual and mechanical updates, keeping GM’s offerings at the forefront of style and innovation. Another of Sloan’s influential ideas was in-house lending. The GM Acceptance Corporation was designed to make auto loans direct to car buyers, opening a profitable new revenue stream for GM and the industry generally.

Under Sloan’s leadership GM continued to expand, purchasing British Vauxhall for $2.5 million in 1925, launching the Pontiac brand (a reimagining of Oakland) in 1926, founding GM’s Art & Color Section in 1927 with Harley Earl heading up design, and acquiring Allison Engine Company and an 80 percent stake in Opel in 1929.

The Great Depression was, of course, a major challenge for GM. Its stock price fell from a high of $111 per share in 1929 to just $8 per share by 1932. Of course, those economic headwinds blew for all automakers. Amidst the turmoil GM not only managed to surpass Ford as the US’s largest automaker in 1931, but it also grew to the largest corporation in the world.

This was also the period of rapid unionization as workers sought higher wages and better working conditions. The Flint sit-down strike of 1936-37 was UAW’s (United Auto Workers) first major strike against a US automaker. Sloan was reluctant to employ the kinds of physical intimidation tactics that had earned Ford negative press; this despite a sit-down strike involving the occupation of the factory floor by workers to prevent operations. Things did, however, turn violent at the Fisher Body Plant in St. Louis when police attempted, and ultimately failed, to clear the factory of striking workers (14 injured by gunfire though none fatally). At the urging of President Roosevelt, GM officially recognized the UAW as the sole negotiating representative for GM workers, instituted a five percent pay hike, and granted permission for workers to talk in the lunch hall.

Sloan’s influence at GM expanded yet further in 1937 when he was named chairman of the board in addition to his role as CEO. He continued in that dual role through 1946 when Charles E. Wilson succeeded him as CEO and remained chairman of GM’s board until his retirement in 1956. The post-war period was an especially fruitful time for GM. Sloan’s emphasis on innovation spurred not just GM but its chief competitors Ford and Chrysler to new heights in the post-war era.