Renewed shocks to global supply chains ensure car and gas prices aren’t coming down anytime soon.

The Good and Bad of Interconnection

Driving a car in the US has been getting more expensive lately. Both gas prices and car prices have risen substantially over the last year. The latter stems largely from the car chip shortage dogging worldwide automobile manufacturing and doesn’t look to be resolved anytime soon. Meanwhile, gas prices spiked in March to their highest level in 14 years and, while global oil prices have trended back downward, prices at the pump have not.

A globalized economy has proven a massive boon for economic growth worldwide, raising the living standards of billions of people. But today we’re seeing some of the unintended consequences of all this interconnection. Problems are no longer localized as ripple effects radiate around the world. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and renewed COVID-related shutdowns in China might feel like a world away, but they’re having tangible effects right here in the US on car and gas prices.

Chip Shortage, In Short

As we’ve covered here, the global supply of microchips suffered serious disruptions over the last two years. The effects have been felt especially hard in the automotive sector. As auto manufacturers idled plants and paused production in 2020, they canceled their orders for the microchips used in everything from power seats to ECUs to infotainment systems. When demand for cars picked back up last year, those chip suppliers, mostly based in China and Taiwan, had found new buyers, leaving automakers unable to get chips into vehicles and vehicles out the door. The resulting mismatch between supply and demand has led car prices, both new and used, to go up, way up.

Gas Prices Spike

Similarly, in 2020, oil prices had dipped into negative territory as demand cratered during worldwide lockdowns. As a result, oil production was slowed. But as demand has returned to normal levels, production has lagged behind. This has meant higher oil prices. That’s good for OPEC, Russia, and other petrol states but puts the squeeze on the rest of the global economy, including on US consumers.

New Complications

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has exacerbated both problems. Western sanctions on Russia have yet to include energy exports, but the volatile situation in early March led to a significant upswing in oil prices, topping out at $130 a barrel. And while oil prices have since come back down to around $100-$110 per barrel, gas prices in the US continue to remain high, down slightly from March’s high of a $4.35 per gallon average to $4.15 today. Local prices, especially on the West Coast and the Mountain West, are still often exceeding $6.00 per gallon.

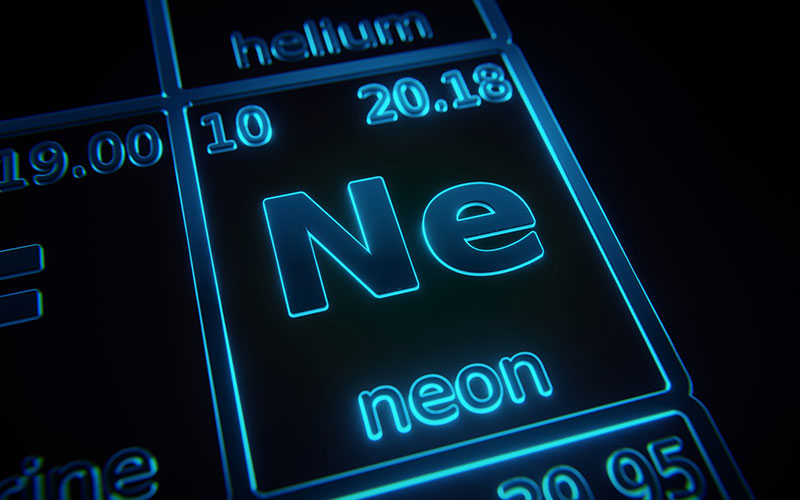

The global chip shortage was also directly affected by the war in Ukraine. It turns out Ukraine supplies around 50 percent of the world’s neon. Neon is used to stabilize the lasers used in microchip manufacturing. In the lead up to the invasion, chipmakers began stockpiling neon in anticipation of a shortage. Industry experts estimate chipmakers have around a one-to-six-month supply of neon currently in reserve. Even with neon recycling and manufacturing modifications, these stockpiles will only last so long. The neon squeeze threatens to deepen an already entrenched microchip shortage.

Near Term Pain, Long Term Solutions

The car chip shortage won’t be solved overnight. In the US, the Chips for America Act is making its way through Congress and would devote $52 billion toward expanding domestic microchip manufacturing. Over in Europe, the European Commission is pouring a combination of public and private funds totaling $43 billion into similar efforts. These funds will help gird manufacturers against another chip shortage in the future but given the time it takes to get such operations up and running, they’ll have little to no effect on the current car chip shortage. The best estimates put us well into 2023 before the chip shortage abates.

This past Wednesday, oil executives were called to Capital Hill, ostensibly to answer for the current price of gas. Democrats placed blame on oil company profiteering while Republicans decried a White House energy policy too focused on decarbonization. The truth was somewhere in the middle. Expanding production faces headwinds from the cost of investment (and uncertain profitability) to regulations, current and future. Getting US oil companies to forgo record profits for the good of consumers is a big ask in a capitalist society. (For more on what’s behind high gas prices, click here.)

Eager to avoid high gas prices, car shoppers are embracing EVs and hybrids like never before. While overall automotive sales were down 15 percent industry wide in the first quarter, EV sales were up 37 percent. Tesla’s numbers were up 87 percent year-over-year, Hyundai’s EVs were up 29 percent, and Polestar was up 1,179 percent, thanks to the debut of its new Polestar 2. (Here are our picks for the best new EVs on the market.)

Even switching to EVs, while wise, won’t inoculate us from the supply chain shocks. EVs use microchips too; and it’s not just neon but the supply of minerals like cobalt, nickel, lithium, and palladium that can seriously disrupt global automotive and EV manufacturing. In the near term, a globalized world economy will remain susceptible to such shocks, even as individual countries move to become more self-sufficient.