Hurst, Holley, and Edelbrock: Legendary Aftermarket Parts

We go back in time to show you how Hurst, Holly, and Edelbrock broke into the performance game and where their legacies stands today.

Edelbrock

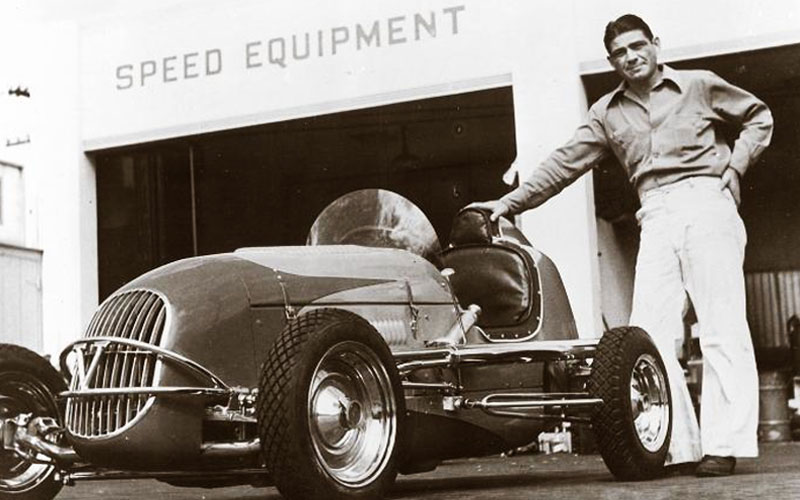

Southern California has seen many dreams fade away as quickly as the sunset, but for Vic Edelbrock, the story would be quite the opposite. He set up an automotive repair shop in Los Angeles in 1934 simply in hopes of finding relief from the Great Depression. He was young but deeply passionate about cars and racing. During the work week he’d fix other peoples’ cars on the corner of Venice and Hoover, but on the weekends he was racing.

He didn’t have aspirations to become some giant multinational performance parts manufacturing brand. Robert E. Petersen once said, “Vic Sr. told me he didn’t want to grow too big because he felt he would lose control and not be able to stay on top of development of new product.” Clearly, that ended up not being as difficult as Edelbrock had thought it might be.

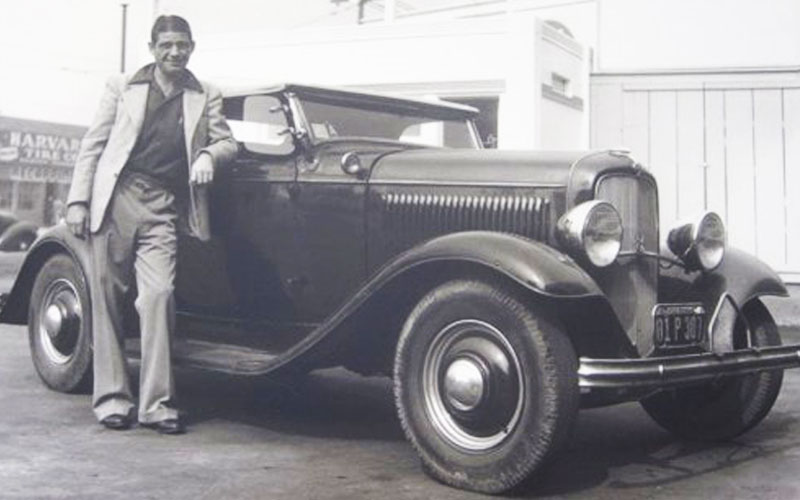

Despite that, it was clear from his work that Edelbrock knew a thing or two about making cars go faster. In 1938, he bought a 1932 Ford Roadster and utilized it both as personal transportation and as a test vehicle. When an initial prototype intake he co-developed and dubbed the Thickstun underperformed, he kept at it. His second iteration leveraged two Stromberg 97 carburetors along with a 180-degree manifold for Ford Flathead V8s.

It was a smashing success and while World War II would cause Edelbrock to shift gears to making aircraft parts, he continued his personal development work on the side. During that time, he came up with an innovative aluminum cylinder head design that would ultimately bring him fame inside of the hot rodding community. In 1946, business was so good that he launched the first ever “Edelbrock Power and Speed Equipment” catalog.

Over the years, he continued to innovate and became a staple across many racing and hot rodding events. In 1955, he was responsible for the first Chevrolet small block engine with one horsepower per cubic inch. After passing away due to cancer in 1962, his company continued under the leadership of his son Vic Jr. The younger Edelbrock continued to innovate by crafting products for the import crowd and partnered with Garrett Turbochargers to create boosted packages that offered even more power.

Now, some 85 years later, Edelbrock is owned by the conglomerate Industrial Opportunity Partners and continues to innovate using the latest and greatest technology. For the most part, it still focuses a lot of its energy on intake manifolds, carburetors, and cylinder heads but it’s branched out, too. It also makes superchargers and other ancillary parts for engine building.

Holley Carburetors

Long before Edelbrock got his start, the Holley brothers, George and Earl were hard at work crafting their own destiny. In fact, they were creating their own automotive parts before the turn of the century in 1900. The two built a car and then, in 1901, released what they called the Holley Auto Bike. In between those years, something very important happened. The brothers acquired a license to build and sell a French carburetor known as the Iron Pot in the United States.

By 1902, they were so successful at it that Henry Ford himself convinced the brothers to focus on building carbs instead of cars. They went to work providing the carburetors for the famous Model T and then sold the business in 1904. That didn’t stop them from going out and designing their own unique carb though and after another decade plus of success at that venture Ford bought them out in 1917.

The pair once again re-entered the business though and in 1938, Ford asked if the parts supplier would use the plans (which Ford owned) from another company, Chandler Groves, to create the same part for less cash. Holley agreed and the Holley 94 was born. For the next 19 years, Holley would produce no less than 17 variants of the 94 and supply Ford with them the whole time.

During that span, Holley also developed its first four-barrel carb which debuted on the 1957 Ford Thunderbird. The team continued its innovation and in 1965, made a deal with Chevrolet to supply carbs for the Z16 Chevelle. Sitting atop a 396 cubic-inch engine, a Holley 4150 carburetor helped develop 375 horsepower. That same 4150 model ended up being a mainstay on other classic cars like the Boss Mustang and the Shelby Cobra.

Today, Holley doesn’t supply brand-new performance carburetors for OEMs but it’s still pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. As engines are getting bigger, “Holley is responding with bigger carbs,” says Bill Tichenor, Director of Marketing for Holley. In addition, it continues to improve the design of its products by introducing lighter materials, additional safety features, and more. It’ll even sell classic parts and replacement pieces to those that need them. Today, Holley serves as a parent company over a number of performance brands and is itself a subsidiary of Sentinel Capital Partners.

Hurst Shifters

Today, the Hurst name is synonymous with shifters but the company didn’t start off that way. In fact, it’s the youngest of the three companies here by some margin and began life as a simple auto repair shop in 1958. The two last names of the founders, George Hurst and Bill Campbell served as the company name. The pair quickly shifted from fixing cars to crafting large aftermarket bumpers for the Volkswagen Bus to finally focusing on piston-driven gear shifters.

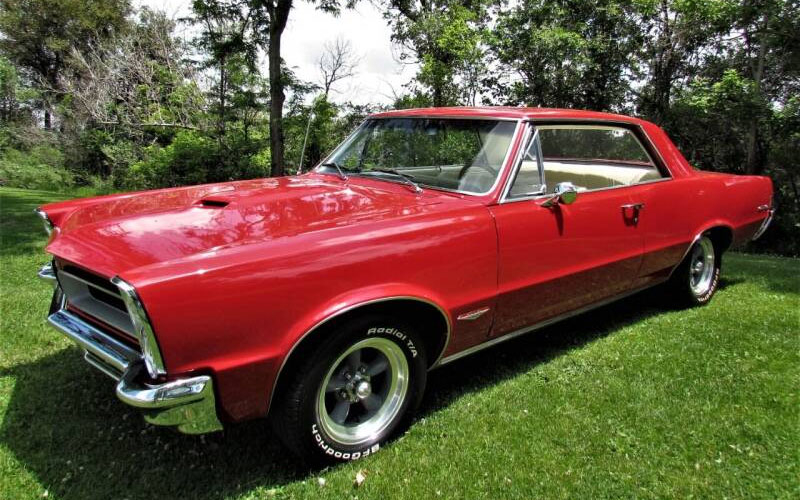

In just two years, Hurst shifters became a mainstay in the performance automotive world. Where most stock units proved somewhat sloppy and flimsy, Hurst shifters were well-regarded as basically unbreakable no matter how hard one used them. Hurst earned contracts not only to supply racing organizations like NASCAR but also to supply OEMs like Pontiac. By 1965, the Hurst name was big enough that GM bent its policy of using outside vendor names on its products with the introduction of the Pontiac GTO.

Over the next few years, Hurst shifters became even more synonymous with reliable performance applications. They ended up in muscle cars like the AMC AMX, the Chevrolet Camaro, and the Plymouth Roadrunner. By 1970, Hurst had gone public and Sunbeam swooped in to take it over. Before he left the company though, George finished one final product, the “Hurst Rescue Tool.” Today, we know it as the “Jaws of Life.”

Since then, Hurst shifters have slowly but surely fallen out of OEM product lineups. The company traded hands multiple times before B&M Performance, a shifter company even older than Hurst, bought it in 2007. Interestingly enough, B&M is owned by Holley Performance Products.