Pete Brock had a knack for automotive design that produced two of the most memorable racing cars ever, the C2 Corvette and the Shelby Daytona.

Making Your Mark

Few automotive designers get a chance to create one automotive legend. Pete Brock designed two: the second-generation Chevrolet Corvette and the Shelby Daytona Cobra. In retrospect, Brock has proven to be one of those excessively talented people who can leave an indelible mark on one profession only to move on and find major successes in whole other arenas. If you have never heard of Pete Brock, allow us to explain what makes his contributions so special.

GM’s Design Prodigy

Pete Brock wanted to design cars. So, the young Californian set his sights on the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Unfamiliar with the college application process, one day Brock just walked in and asked if he could attend. He was told he would need a portfolio to submit as part of his application. Brock had to ask the receptionist what a portfolio was. Once it had been explained to him, Brock went back to his car and drew up sketches, enough that in an hour or two he had a portfolio to submit. Despite his hasty preparation, Brock was accepted.

It did not take long for Brock’s talents to be recognized. He was picked out of class by GM headhunter Chuck Jordan at the age of 19 to work with the company’s design team, making him the youngest designer ever hired at GM. Brock arrived at an auspicious period in the late 1950s, a high watermark for automotive design when GM’s design team was headed by none other than Harley Earl, soon to be succeeded by another future design legend Bill Mitchell.

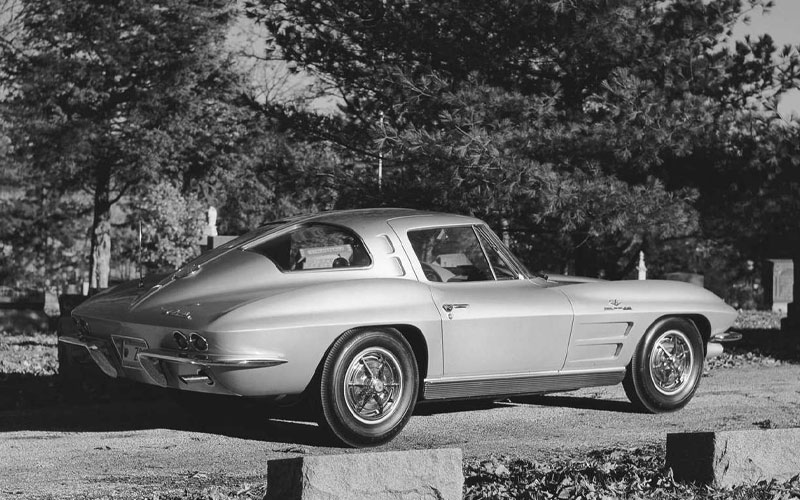

At that time, the first generation of Chevrolet Corvette had been struggling. Even with the addition of a V8 engine in 1955, the Corvette was consistently being outsold 15-to-1 by the Ford Thunderbird and GM was seriously considering canceling the car altogether. Bill Mitchell had other ideas and solicited designs for a succeeding generation to redeem the Corvette.

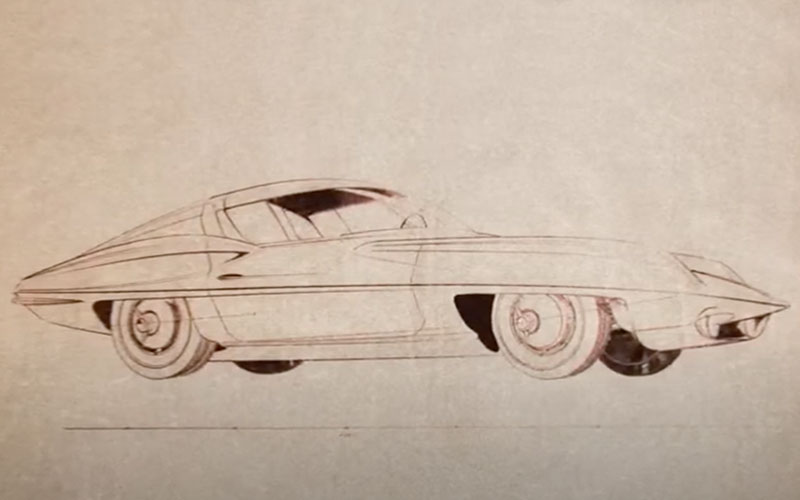

Among the submissions, Brock’s 1957 sketch stood out and Mitchell chose it as the basis for the new car. Brock’s design would be used for the XP-87 prototype aka the Sting Ray Racer. Designer Larry Shinoda built off Brock’s design, further refining it for the eventual road car, the second-generation C2 Stingray Corvette which would debut in 1963. Between Brock’s work and that of Shinoda, Zora Arkus-Duntov, and others, the C2 Corvette would indeed redeem the nameplate and ensure its survival.

Designing the Daytona

In the meantime, Brock left GM and returned to California in 1959 (at the age of 21) to pursue racing (he was finally old enough to get his SCCA license). It was through racing that he met Carroll Shelby. Shelby hired Brock to run his Carroll Shelby School of High-Performance Racing and work at Shelby American. In fact, Brock was Shelby’s first employee.

Brock put his designing skills to work at Shelby American, designing liveries, ads, and logos as well as racing, the De Tomaso P70 and Daytona Cobra among them. It was the latter of those two cars that would cement Brock’s reputation in the car world.

Carroll Shelby, one time winner of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, wanted to make a run at the European GT circuit. The only problem, the AC Cobra did not have the top end speed necessary for the long, high-speed straightaways typical of those tracks. The Ferrari 250 GTO, which had been dominant in recent years, could reach 174 mph on Le Mans’ Mulsanne Straight. The AC Cobra lacked the necessary aerodynamics, given its open cockpit, and top speed peaked at 157 mph. Brock knew the Cobra needed a new body if it was going to beat the Ferrari 250 GTO. But the prospect of a new car with new aerodynamics was cost prohibitive for Shelby American.

Pete Brock found a solution. He identified a rules carve-out, Appendix J, that allowed for comprehensive body alterations on a previously homologated vehicle. No new car would be needed after all. This meant Brock could implement new aero as he pleased.

Aerodynamics was just coming into vogue in automotive design, but it had been the subject of study decades earlier in Germany prior to WWII. Brock had studied the work of engineers like Erwin Komenda (of Porsche) who’s papers on aerodynamics had been collected by the Allies after the war and disseminated to American carmakers, allowing Brock to find them in GM’s archives.

The innovative design for the Cobra lowered the hood, altered the gaping intake at the front of the car, enclosed the cabin, flattened the rear of the car, and added a ducktail spoiler.

Breaking Record After Record

Brock, along with coachbuilder John Olsen and test driver Ken Miles, further refined the new car over a month’s time. In early testing, Miles broke the Riverside Raceway lap record, and in the process hitting 186 mph (steering, however, felt light above 160 mph, yikes!).

In the car’s first race, at Daytona in 1964, the new Cobra set another lap record and was poised to win but a pit fire forced it to retire. From this race on the car was dubbed the Daytona Cobra. At the 12 Hours of Sebring, the Daytona Cobra set yet another lap record and netted a GT class win. This was the first of a succession of high-profile wins for the Daytona Cobra including at Le Mans in ’64, the 24 Hours of Daytona in ’65, Sebring again in ’65, the Italian GP at Monza in ’65, the Nürburgring 1,000 km in ’65, the 12 Hours of Reims in ’65, and the Enna-Pergusa in ‘65. The car then set 25 land-speed records at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah.

It was one of the most spectacular runs for any racecar ever. Today, the Shelby Daytona Cobra is one of the rarest, most prized, and most expensive collector’s cars in the world. (Read more about it and its rival the Ferrari 250 GTO here.)

Racing and Hang Gliders

In 1965, Brock founded Brock Racing Enterprises which did racing design work for companies like Toyota, Datsun, and Hino. Starting in 1969, Brock Racing Enterprises became the factory team for Datsun in the SCCA DP class and later in Trans Am (starting in 1971).

As much as Brock loved racing, he also loved hang gliding and in 1970 he founded Ultralite Products making parasails and hang gliders. The company, like so many of Brock’s efforts, was a success and he eventually sold out of the company in the mid-1980s.

Brock went on to teach at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena no less and worked for over twenty years as a photojournalist covering endurance racing. Today he resides in Henderson, Nevada near Las Vegas.