Car Assembly Lines: How They’ve Changed

The car assembly line revolutionized the automobile industry more than 100 years ago. Find out how it started, and how the process evolved since then!

A Faster Way to Build Cars

Where would the automobile industry be without the assembly line? The innovators of the late 19th century would’ve likely found a way to advance the construction of automobiles, but the assembly line certainly sped up the process. It’s something we take for granted today, but the implementation of the assembly line revolutionized the automotive industry over 100 years ago. Who created the system? What automaker was the very first to use it to build vehicles? Learn about that, and how the process is evolving even today, by continuing on below.

The Inventors and Their Inspirations

Henry Ford gets a lot of credit when it comes to being an early inventor of the automobile, and using the assembly line to fast-track production of vehicles like the Model T, but he wasn’t the first automaker to mass produce vehicles. When Karl Benz developed a gas-powered automobile in 1887, he made several identical replicas of it. That can be counted as the first production vehicle.

Then there is Ransom Eli Olds, the founder of Oldsmobile, who created the assembly line to mass-produce the Oldsmobile Curved Dash. He started using a stationary assembly line process in 1901. The next year, Olds hired the Dodge brothers to build 3,000 transmissions for the Olds Motor Vehicle Company.

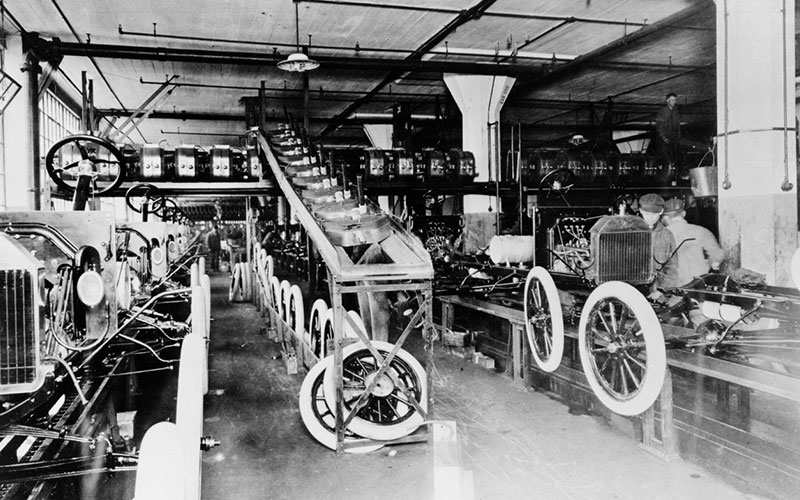

Ford may not have been the first, but he wasn’t far behind. He was already developing vehicles at the same time Olds was making the Oldsmobile Curved Dash. By 1908, Ford was making the Model T. After some trial and error, on December 1, 1913, Henry Ford ushered in a new era in automobile manufacturing by becoming the first to use the moving assembly line at his Highland Park assembly plant. Instead of moving workers from place to place, he moved the automobile to them. Ransom Olds provided the blueprint, and Henry Ford took it to the next level.

Clear Benefits of Car Assembly Lines

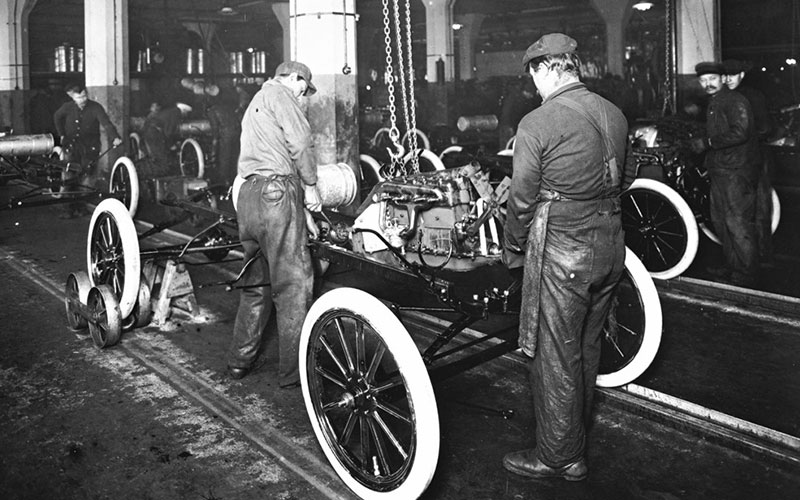

Once Ford added a moving element to the assembly line, production became quicker than ever before. A Model T could now be built in just 90 minutes! A rope was used to pull the vehicle down the line, and workers built it part-by-part. Later, a chain mechanism was used to push vehicles along.

Quicker, and less expensive than other options, the assembly line method was adopted by other car builders, too. William R. Morris tried to emulate Ford in Britian. Louis Renault did the same in France. By 1915, Chevrolet, was operating the famed General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan. Dodge had a plant in Hamtramck, Michigan, too.

There Were Some Drawbacks, Too

This streamlined building process didn’t make everyone happy though. Some workers began to quit their jobs at Ford because they were bored. They shifted from building the entire car to handling just one or two parts of the vehicle construction. The timing was also very important in assembly line production. Every task had to be completed in a certain amount of time before the car moved down the line to the next station.

To prevent additional employee departures, Henry Ford added a profit-sharing element to his employee’s wages, doubling their wages to $5 a day. The idea of higher earnings brought workers back to the Detroit plant. Ford also decreased employee shifts by an hour, and then created a third shift so that his plant could roll vehicles out the door outside of the traditional workday.

One other result of the assembly line was that Model T’s and other Ford vehicles couldn’t be varied much. There wasn’t time in the process to add any custom elements. Each car being made was the same, and relatively basic at that. To make up for that, Ford reduced the cost of the Model T touring car by $590. He was selling it for less than half of what he did before he started using the moving assembly line.

Modern Car Assembly Lines

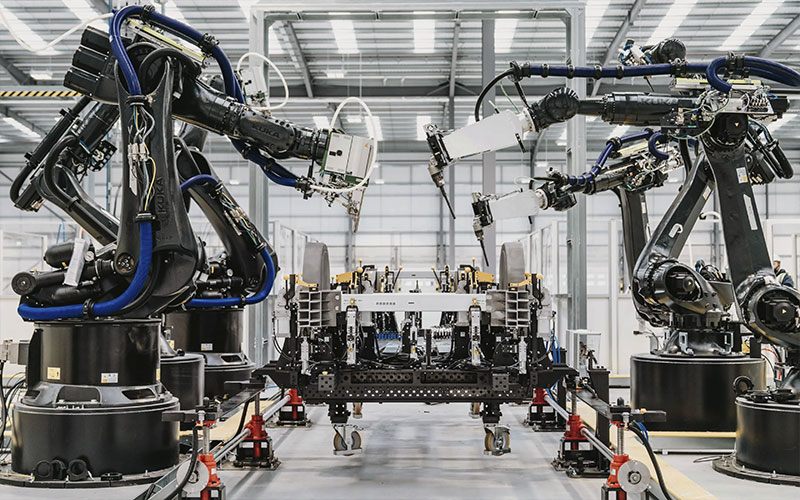

The assembly line is still alive and well today. In fact, it’s still very similar to the way it was a century ago. Vehicles still go down the line, making stops at each workstation. Though there haven’t been drastic changes to this process, it has been refined. There’s more automation than before. Machines are able to do work that was required of humans as recently as a couple of decades ago.

Another difference is that parts that weren’t made in the plant are used to assemble vehicles in that plant. Parts come from all over and are then used to put the vehicle together. Today, in order to be considered a vehicle that is made in America, at least 75% of the parts must be made in America as well.

Automakers like Toyota and Honda invested millions in parts and jobs at factories like the Honda Accord facility in Marysville, Ohio, or the Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky plant in Georgetown, Kentucky in order to achieve that ‘made in the U.S.A.’ status. Since it opened in 1986, the Toyota plant in Kentucky has assembled more than 579,000 vehicles. Approximately 7,000 employees work there today. It’s a similar situation with Nissan, Kia, Volkswagen, Subaru, and Volvo.

A Newer Way of Building Cars

As more and more automakers are entering the electric vehicle realm, they are also expanding their own production abilities and facilities. They’re not just assembling vehicles these days. They’re also assembling batteries to go in those vehicles. General Motors, for example, has invested billions in all-new facilities like the Wallace Battery Cell Innovation Center, to expand their battery technology operations. Tesla already opened gigafactories in Texas and Germany to supply battery packs for company EVs, and now it’s evaluating whether or not a lithium hydroxide refining facility on the gulf coast of Texas is feasible.

Other companies are taking yet another approach. Arrival, an EV company backed by UPS, is creating, “micro factories,” where delivery vans and buses can be assembled by robots. They’d produce tens of thousands of vehicles (less than a traditional auto plant). They plan to take the decentralized factory method into areas that have the most demand for product while using existing commercial spaces to assemble their vehicles.

The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same

A lot has changed in the automotive industry in the last 110 years. The materials used to make cars, the energy that runs them, and the builders who make them have all changed. So has the demand for certain body styles and the quantity of vehicles that can be produced in a given period of time. The concept of the moving assembly line, however, has not.

While some of these new innovators reimagine the assembly line, incorporate more robotics, and work to refine the entire process, the basic idea of mass-producing vehicles by moving them from one location to another doesn’t appear to be going anywhere anytime soon.