The Bill Thomas Cheetah: Chevy Legend

In the annals of American sports-car-racing, the Bill Thomas Cheetah stands out thanks to radical design and serious Chevy power.

Bill Thomas and the Chevy Cheetah

It’s hard to overstate how crazy the car culture of Southern California was in the 1960s. Hot rodding, drag racing, road racing, and all manner of customization were running wild, something you can get a sense of in our Kustom Culture article. It was here that Carroll Shelby, a true automotive legend you can read up on here, teamed up with Ford to knock Ferrari from its perch atop the international racing scene. They were awfully successful with cars like the Cobra 427, an absolute brute of a car we dive into with this Retro Review. Of course, cross-town rival, General Motors, wanted in and thus, the Bill Thomas Cheetah was born.

Effectively a self-taught engineer, Bill Thomas earned the moniker “Mr. Corvette” thanks to some 100 racing victories piled up by ‘Vettes he had modified. This caught the attention of GM, who ended up contracting with Thomas as an in-house performance specialist. He prepped Biscaynes for drag racing and stock cars for NASCAR, amongst other projects, becoming a tuner industry pioneer in the process. Were he around today, his skills would no doubt land him in the same circles as SVT and AMG, factory hot rodders we highlight here.

But it was the Bill Thomas Cheetah that would become the signature result of this partnership. It was the early 1960s, the heyday of Southern California sports-car-racing. Shelby was on a tear and Chevy was looking to compete. However, for a variety of reasons, GM instituted a ban on corporate racing at about the same time. Undeterred, Thomas connected with GM executive Ed Cole to pitch him on a car that could catch Shelby’s Cobra – the Cheetah.

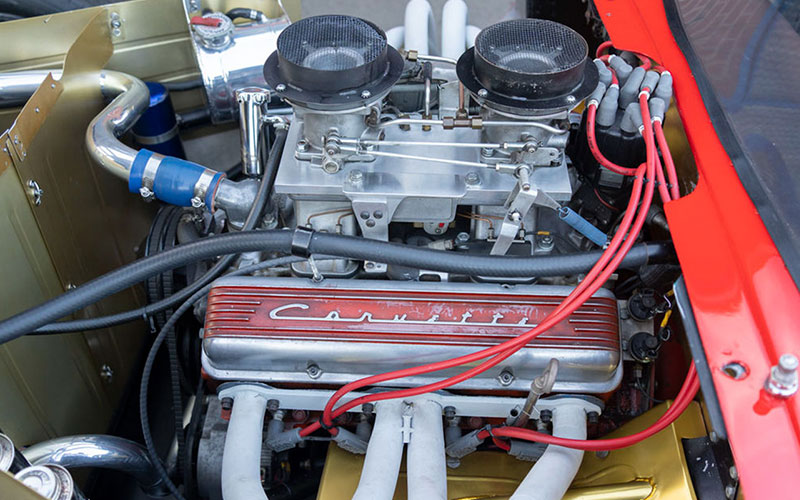

Approved by Cole, with the understanding that this skunkworks project would move forward behind the scenes, Thomas got to work sourcing the running gear through his racing connections. A Corvette 327 would provide the power with a Muncie 4-speed transmission and Corvette suspension assemblies coming together to form the running gear. From here, Don Edmunds penned a design that would lead to a prototype after just a few simple sketches. A key note, that would go on to impact the future of the Cheetah, is that this project was intended to be a styling exercise that Thomas could parlay into ongoing contract work with GM. It was not designed as a race car.

The first Cheetah prototype wore aluminum sheet metal around a relatively radical powertrain layout. Namely, though this was technically a front-engine design, the motor was mounted so far to the rear that there was no need for a driveshaft. Instead, the connection between transmission and differential was simply a universal joint. This led to a second issue that would come to haunt the Cheetah – a stifling driver’s compartment. Because the engine was pushed into a near mid-engine position, the driver’s legs were right next to the motor, which had the exhaust headers – that get ripping hot at speed – routed up and over those legs.

Though not designed for racing, Thomas ran a performance show-and-tell with GM brass at Daytona to prove the Cheetah’s worthiness. The car hit a staggering 215 mph. Along with cutting-edge design, the car only weighed about 1,500 pounds and had a thundering Mr. Corvette special under the hood. Needless to say, Thomas received the go-ahead on building more.

A second aluminum-skinned Cheetah was to debut at the 1963 Grand Prix in Los Angeles but crashed in practice. It received a new fiberglass body, showing up to race at Riverside International Raceway in 1964, but also spinning out into a crash. This car would go on to be raced by Jerry Titus, eventually appearing in the Elvis Presley film Spinout.

The following eight documented Cheetah builds stuck with a fiberglass body over a TIG-welded chrome-moly tube frame. Between 1964 and 1965, these cars were raced with quite a bit of success, including 11 regional event wins and strong showings in the US Road Racing Championship and Federation Internatinoale de L‘Automobile races. However, because the Cheetah was not designed to race, it struggled with long-term success. Engine overheating due to a lack of heat extraction vents was one issue. Overheating of the driver’s themselves led to one car being converted to a roadster to avoid head exhaustion.

Then there was the notable lack of chassis rigidity required to keep the Cheetah competitive on the twisty transitions of road course racing. Under these rapidly shifting loads, the suspension geometry was actually changing on the fly, making it extremely difficult to handle even for veteran racers. Adding more power led to more handling problems like trailing arms flexing outward under wide-open-throttle that could cause the rear wheels to toe in. Some owners added their own chassis gusseting or all-new suspension bits to address this, but the fact that the Cheetah was built mainly as a proof-of-concept meant it couldn’t keep up on the track.

Ultimately, the Bill Thomas Cheetah hit the proverbial wall when race rules changed in 1964. Previously, only 100 cars were needed for homologation but going forward that number would spike to 1,000. There were other factors at play like a fire at the Cheetah factory and GM withdrawing its financial support of the project. All of which made the likelihood of producing 1,000 vehicles effectively impossible. And so, Bill Thomas shut off the lights on his Cheetah and moved on to other projects.

Though official numbers are murky due to a lack of clear historical records, most estimates point to a total of 23 total Bill Thomas Cheetahs being produced with only 10 or 11 delivered to customers. The rest appear to have been in various states of completion prior to that factory fire. Even though the Cheetah would unfortunately never go head-to-head with the Cobra in a high-profile officially sanctioned competition, it would go on to become a seriously sought-after collector’s car. One of the original 10 cars sold at auction in 2018 for a whopping $718,750.